Background to the Parish of St. John the Evangelist, Allerton Bywater

Foreword to:-

A GARDEN BY CHANCE

I was delighted to read Father Hargreaves’ history of the Parish of St. John the Evangelist at Allerton Bywater. He has clearly gone to great trouble to do so, and if other parish priests follow his example, there would be a most interesting documentation for future generations.

It is always helpful to know the historical background of the places in which we live and I feel sure that the people of St. John’s will derive a greater understanding of the developments of their area from this admirable little production.

Father Hargreaves’ aim in writing it was to try and make the older inhabitants accept the new-comers and to make the new-comers willing to be accepted and to enter into the community. This little book indeed should help to develop a sense of community responsibility and a deep affection for the traditions of the area, and it is my prayer and good wish that this would happen.

I hope that all new-comers to the area will be able to read this history and I hope that in future it will be shown by the Parish priest of Allerton Bywater to the Bishop and all his successors when they come on Visitation so that they may know how things have developed in the wonderful providence of God.

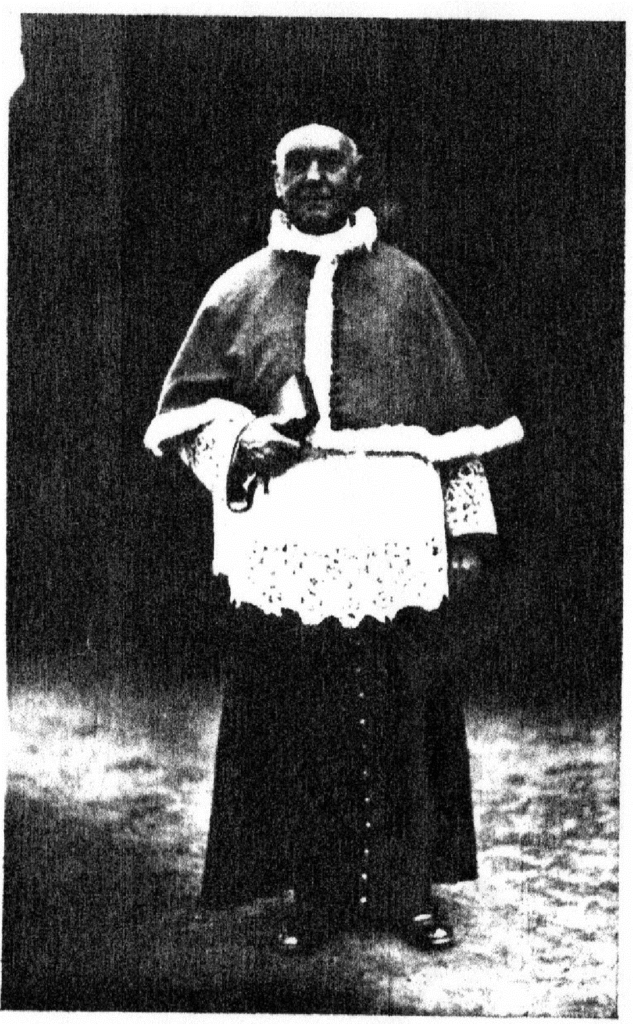

Wm. Gordon Wheeler, M.A., Bishop of Leeds.

A GARDEN BY CHANCE

Background to the Parish of St. John the Evangelist, Allerton Bywater.

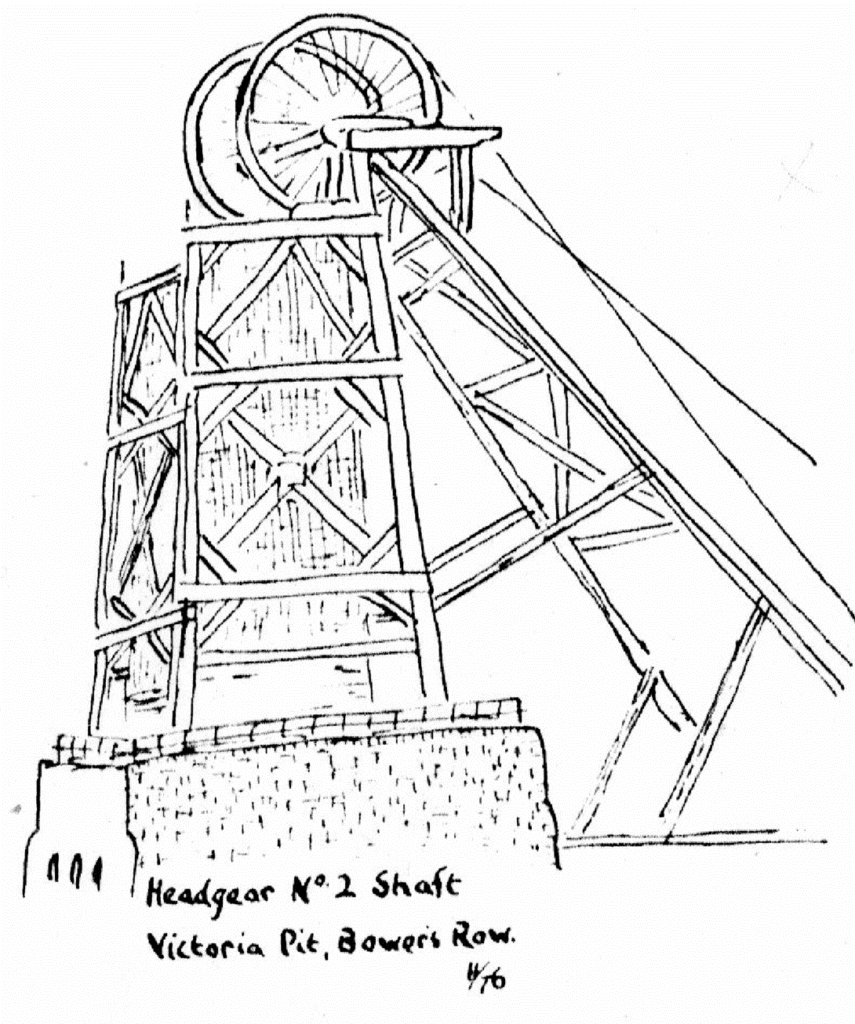

The Johnny Pit winding gear was quiet, for a change.

Down at the foot of the hill the pumps of Middle Pit were working to keep all the shafts and levels free from flooding. but the barnyard noises from down the street could easily make you forget where you were.

This was how it had sounded in the old days, when all around here was woodland and farms, when the larks and the woodpigeons could make themselves heard on weekdays, before the Lowthers opened the mine down the hill, before Joshua Bower and Company opened their Victoria Pit and their Albert Pit (but we had our own names for them), and before Bowers built these rows of red brick miners’ houses, one shop, no pub.

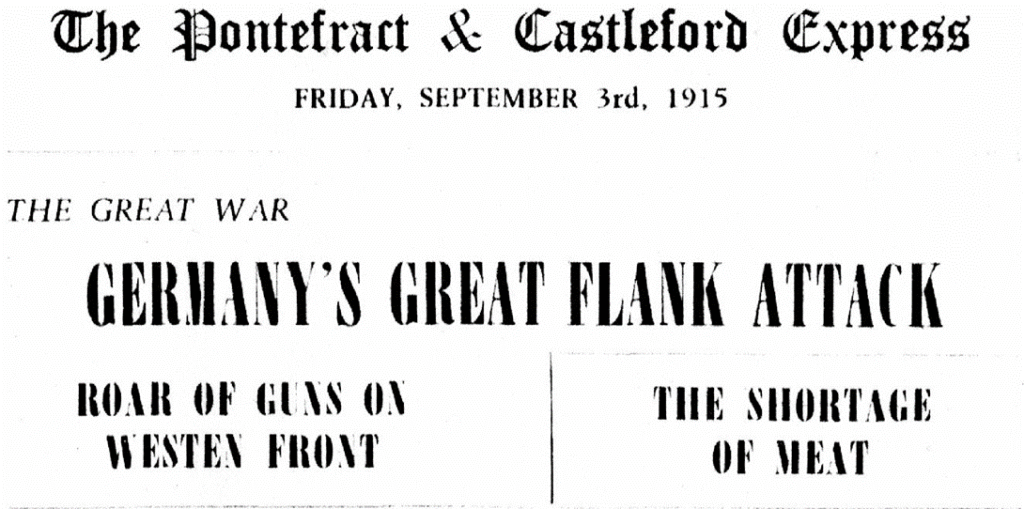

The folk were walking up the hill in their Sunday-best, this 29th day of August, 1915.

Most of the people were making for the chapel on the road which ran by the woods, but a few excused themselves and turned right towards Woodend. Old Mr Sennett was feeling able for the walk this morning and came stumping up from the Cotts; the Connells and the Conellys were walking up Hill Street, the longest row of them all, 37 houses of neat ride, with sandstoned steps and sills to relieve the monotonous brick, up past the one general-store-Post-Office at the top, chatting to the Hessions from 3 Albert Street, joining all the Greaneys who lived in Number One School Street, walking past the school whose bell-cote proclaimed that it had been “erected by Charles Hugh Lowther, Baronet, Lord of the Manor, in the year of Our Lord 1870”. But we weren’t so much interested in the Lord of the Manor – more in seeing of the Riley children were ready to come from Hollinhurst, or in looking out for Dominic Lavin in his gig, trotting down to Castleford.

Down Whitehouse Hill we walked (only you would call it Leeds Road), past the Angel, down Main Street at Allerton Bywater. We picked up Miss Cross, the schoolteacher from Otley, and that young lad from Rhodes Farm whose name we could never remember. On past the Vic, then past the Boat Inn, and along the towpath beside the river, to Lock Lane, over the Bridge into Castleford in time for the 11 o’clock at St. Joseph’s.

We prayed for the safety of our men at the Western Front, we prayed for the glory of God and the souls of the men killed in Flanders; the Canon announced the notice about the laying of the foundation stone of St. John’s tomorrow, and the men who had been on nightshift from Bower’s were able to go to Communion without any fuss, even though it was the late Mass.

Back we came, the way we’d gone, with the McCoans from Kippax for company part of the way; but this time when we got to the Boat Inn, we stopped. The men went in for a drink, the first drink of anything since midnight, and for a chat with Mr Prime. His wife chatted with the women, who brought out a bottle of pop for the children to share. Then back home for Sunday dinner, with all the vegetables out of our own gardens. We’d been used to having a joint of beef every Sunday, too, but just lately the war had been making meat rather scarce. Lucky for us that our Dad kept hens and pigs in his plot between the wagon lines and the houses.

FOUNDATION STONE LAID

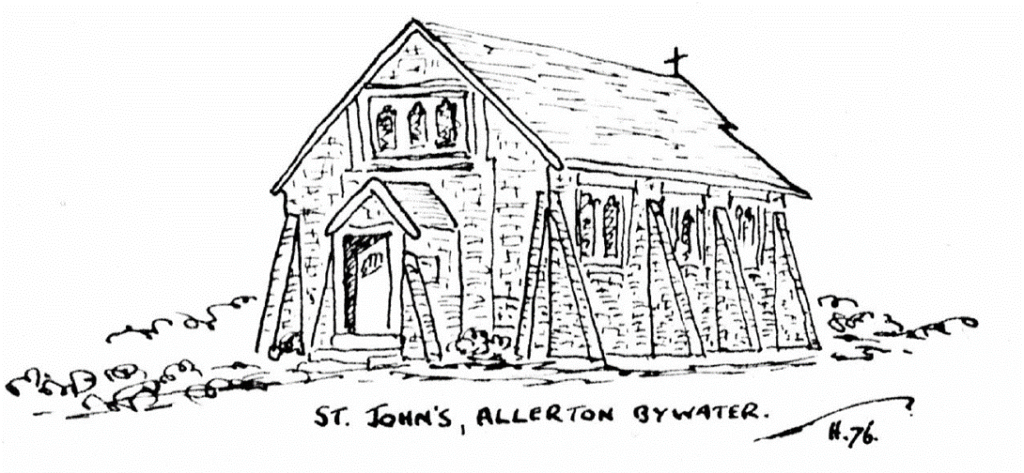

“The adherents of the Roman Catholic faith at Bowers Row, Kippax, Allerton Bywater and Methley all of which are included in the Castleford Catholic Parish, have hitherto had no nearer place of worship which they could attend than St. Joseph’s, Castleford, and the desirability of making provision for them nearer their own homes has been felt for some time. With this object, Canon Hewison, of Castleford, recently purchased a site at Hollinhurst, at a cost of £442, and on Monday afternoon the interesting ceremony of the stone laying of a new church therein was witnessed. The building to be erected will be a substantial brick structure, Gothic in style, and will be to the plans of Ald. A. Hartley, J.P., architect. Accommodation will be provided for 130 worshippers. The nave will be 39ft. long by 21ft. wide., and the chancel 9ft. by 11ft. wide, while the sacristy attached will be 13ft. square. and a small entrance porch is also to be provided.

There will be three windows of leaded lights on either side, and the roof will be supported by open wood- work. The building is expected to cost about £500. The site contains about 900 square yards, and will leave room for any extension which may be necessary in future years.”

“There was a large assembly to witness the stone laying ceremony. The clergy robed in a tent on the field at the rear of the Angel Inn, and a procession was formed to the site which adjoins the main road some two or three hundred yards away. The clergy present were Dr. Cowgill (Bishop of Leeds), Canon Hewison (Castleford), Rev J. Donkers (Castleford), Rev. H Fove (Pontefract), Rev. W. Fitzgibbon (Pontefract). Rev. A. Dekkers (Goole), Rev F. Mitchell Dewsbury), Rev. J. Inkamp (Normanton), Rev. W. Donkers (Mortomley), and Rev. W. Hawkswell (the Bishop’s Secretary). They were preceded in the procession by the crossbearer and acolytes, schoolchildren from Castleford and the district, and members of the church”.

“The foundation stone was solemnly blessed and laid by the Bishop, and bears an inscription in Latin, of which the following is a transcription: To the greater glory of God and honour of St. John, Apostle and Evangelist, Joseph Robert, the Bishop of Leeds, blessed and laid this stone on the 30th day of August 1915”

“An address was afterwards given by the Rev. Fred Mitchell, basing his remarks on the text: Behold I am with you always, even to the end of the world”.

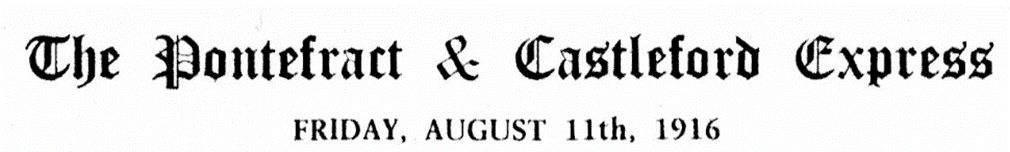

Under the heading “The Great War”, the report was of a Picardy ridge. held against heavy German attacks, the claim of a French advance at Verdun, and a statement about Allied progress on the Somme, mentioning Poziere, High Wood, and Thiepval. There were photographs of the faces. of nine men from the area, one of whom had been recently wounded, the other eight killed. Underneath these photographs, on the front page this time, was the caption “St. John’s Catholic Church, Allerton Bywater”, “The Opening Service”. Then followed a report, part of which repeated word for word the description of the church given at the stonelaying ceremony a year previous, but which added “but now (the Roman Catholics of the area) have a Chapel of Ease in their midst. . . . The church was used for public worship for the first time on Sunday morning (6th August 1916), there being a very large congregation. The building was first blessed by the Bishop of Leeds, Dr. Cowgill, who was assisted by Canon Hewison of Castleford. High Mass was then celebrated by Canon Hewison, the music being rendered by St. Joseph’s Choir.”

“A Sermon was preached by Dr. Cowgill, who said it was a joy to a Bishop to be with his people when a new church was being opened, and it must be a joy to the people to take part in such a ceremony. It was a joy to him to see a home built for God in the midst of His children, when those children had been without a church and the children would have joy because they had built that home. They had done something for God and something for themselves as well. They had given a dwelling place, and He wanted that dwellingplace because it was His delight to be with the children of men. It was for their sake that He delighted to be with them. They had given Him a tabernacle, but He wanted it only as a meeting place between Him and their souls”.

The reporter, possibly a junior one who had still to learn the difference between a transcription and a translation, then went on to give a summary of the sermon, which if the summary is a faithful rendering, would get full marks for triumphalism and none at all for Christian unity. I find it interesting to note his remark that “in the last 30 years in the Diocese of Leeds the number of churches and priests had nearly doubled, and their schools, in spite of opposition and difficulties, were increasing”; (I find it puzzling, though, to read his statement “not one school had been closed or delivered up to the enemy”, unless it refers to the schools belonging to other denominations which were handed over to the state about 1912-?)

The newspaper report ends by saying that Fr. Mitchell “eulogised the courage of their pastor, Canon Hewison, in undertaking that responsibility and said that not many men of his years would have started building churches. It was their duty to show him loyalty, sympathy, and help. Gifts were afterwards placed on the stone and amounted to £30”.

So it sounds as if Fr. Mitchell was a personal friend of the Canon, imported from Dewsbury to preach the sermon. (Both had 20 more years to live). Fr. John Theodore Donkers was the assistant priest at Castleford, the Canon’s first of many curates, and he took a special interest in Bower’s Row. Fr. Willibrord Donkers was his brother, working at High Green near Sheffield. These two men were Dutch, as were Fr. Dekkers and Fr. Inkamp. Fr. Fové came from the French-Belgian border. The Bishop, his secretary, Canon Hewison and Fr. Fitzgibbon managed to be Englishmen.

The newspaper report was confined to the inside pages, since the front page was devoted to dealing with Great War if space had allowed, it could have mentioned the festivities that went on in the White House field, that Monday, August 30th, 1915, behind the Angel Inn the presence of Kippax Brass Band, Mr Gallagher the builder, and the councillors, finishing in the evening with a gala. All the children of the parish were present. One little girl, whose family were, and still are, members of Bowers Allerton Mission, was lost with envy and admiration at the sight of young Rosie Lavin from Great Preston stepping out of her Daddy’s pony-trap in a gorgeous green dress. But the newspaper didn’t mention that it had more sombre things to deal with. In the next twelve months the church would be built at Woodend, throughout the country voluntary enlistment would be replaced by compulsory military training, first of all for single men, then for all men, single or married; mothers and wives would receive the dreaded telegrams, and on one single day. 20,000 British lives would be thrown away in Northern France.

Leeds is the principal seat of the woollen manufacturers of England, and the most populous town in Yorkshire. It stands in the midst of one of the richest mineral districts of the West Riding, containing no less than 102 collieries. These collieries, with the four in the Normanton district produced 2,505,000 tons of coal in the year 1868, which is rather more than the fourth part of the whole quantity of coal produced in the county of York . . . . This immense supply of fuel, besides answering all domestic purposes, and illuminating the town and neighbourhood with gas (in which, within our recollection, darkness was made visible by glimmering oil lamps), also supplies the means of working every variety of machinery, and of carrying on the varied textile manufactures for which Leeds has been celebrated for so many years”.

So wrote the editor of the “Leeds Mercury”, Thomas Baines, 1. in 1870, including in his list of Yorkshire coal mines and coal owners the following from our own immediate vicinity: Allerton Main (Joshua Bower), Allerton Haigh Moor (Locke & Co.), Astley (Joshua Bower), Allerton Bywater (Thomas Carter & Co.), Garforth (Gascoigne & Co.), Foxholes, Methley (William Wood), and Owlet Hall (Mason & Co.) 2.

It is the mines owned by Joshua Bower that concern us most at the moment in the 1860s (I think), that company sank its shafts. The family, firm of Bower had started as a glass-making concern earlier in the century, then expanded nationwide into roadmaking, then into coalmining. Like the other coalowners, they also farmed the land under which their coal lay, to avoid being accused of damaging other people’s property by the consequent subsidence. Again like the other coalowners, they advertised far and wide for workers to come and live in the houses which they were building beside the new mines. This was part of a pattern in the Leeds area the population had more than trebled in the first half of the 19th century, and that rapid increase was still continuing. 3. But Bowers Row was not an expansion of an already existing village it was simply created out of farmland and scrub. Before the Rows were built, there had been a few cottages scattered among the fields that used to lie between Astley Lane and the River Aire, but in those days the population consisted mostly of rabbits, foxes, and skylarks. People were an innovation, and just about every human being was very much a newcomer.

Other places often did at least have some roots and some town tradition behind them Leeds had had its charter since long before Dick’s Days (Dick Oastler had only just been buried at Kirkstall); even if we narrow the outlook to that of the Roman Catholics, Castleford had had a tiny, shortlived Catholic school in 1590, the Aberford area had a Benedictine priest serving it at least from 1725 and ever since, and the Hammerton family of Monkroyd had been able to establish the Jesuit priests in nearby Pontefract in the reign of James II. One of the results of industrial expansion in the North of England between 1800 and 1850 was to bring large numbers of people to live and work in towns, people who previously had worked and lived in the country. 4. Quite a number of these were English Catholics, whose religion had been to a large extent sheltered by the Catholic land owning gentry, and who therefore had been country folk. Now, in the towns, their priests could more easily develop them into thriving congregations, especially where immigration from Ireland helped to swell their numbers or established new communities. But to the village of Bowers Row, everyone was an immigrant, whether from Barnsley or Ballyhaunis – there were no tradition, except that which you brought in your heart. The mines were sunk, people came to work, and the firm built the rows of houses where they could live.

The census returns of 1871 are the first to show people living at Bowers Row. It includes a small number of people who were born in Ireland and who were at least likely to have been baptised as Catholics – James and Ann Duffin were both born in Ireland but had recently come from Nottingham where all their four little girls had been born; Martin and Ann Doyle were both from Ireland but their young son John had been born locally. James Healy had been born in Meath, his wife Catherine of Longford, but their four-year-old Margaret had been born in Sheffield. A few more Irish-born people lived in Great Preston Edward and Mary Kelly, both from Leitrim, William and Mary Wood, and Henry Findlern and Thomas Day, both lodgers. In Kippax the police constable was an Irishman of 24 called John Croskery, whose wife Annie was a Selby girl they had a five month old daughter, Elizabeth. All the above men, except the policeman, were either “coal miners” or “coal labourers”. Further research would be needed to ascertain how many of the other inhabitants were christened R.C.s.

In the baptism registers of St. Joseph’s, Castleford, which begin in 1881, there start to appear the surnames of people who definitely have descendants still living in the parish these were a nucleus of about half-a-dozen families who originated around Dunmore in County Galway the Greaneys, the Hessions, the Connells, the Connellys, and the Rileys — these folk already knew each other back in Ireland, and started to come over before 1880. The boys would make their first boat trip about the age of 16, unable to afford trousers and dressed in a home-made kilt. In later life they would recall how they came over in petticoats”. At first they worked on the farmland belonging to the mine, quickly earning enough for a pair of pants, and they might or they might not return to Ireland after the harvest. Gradually some of them settled, in penny numbers, and managed to get jobs at the pit and a place to live among the Rows.

John Riley came from Dunmore, lodging first of all at Farren’s Yard near the Ha’penny Bridge over the River Aire on the path to Methley. He eventually got a job as an engine driver at Bowers, and married Mary Madden from Shannon Street, Leeds (just behind the Woodpecker Inn on York Road). The wedding took place at St. Patrick’s Leeds, and the couple set up home at 2 Wood Street, later moving to Hollinhurst when these were built about 1900.

Dominic Lavin, who lived at Great Preston, was born at Ballymote in County Sligo about 1849. He came to England as a teenager about 1864, and after a short circus career (he wrestled bears !), he got a job sinking Bowers mines, eventually marrying at Batley a Scots-Irish girl from Batley named Ann Gordon. They settled first at Side Row, Great Preston, then, again about 1900, they moved to the newly-built Helena Street in Kippax.

The young John Greaney had an aunt and uncle who had lived at Owlet Hall, Kippax, before moving to Great Preston (and later to Barnsley). He lodged with them, courted Mary Ann Conroy from Horsforth, and married her at St. Wilfrid’s, Aberford, the church built towards the end of the Penal Days and served by the Ampleforth Benedictines.

There was no Mass-centre in Castleford until 1877, so the Catholics of our area went to Mass and had their children baptised at either Aberford, or Hunslet, or Wakefield (some of them were working on farms near Wakefield), rather than at Pontefract where the priests looked after Castleford; to me all this suggests that there were ties with Leeds, either of kin or of communication, even though when St. Joseph’s, Castleford, was begun in 1877, for the first three years or so it was served by priests from Pontefract, who by now were secular clergy instead of the Jesuit Fathers.

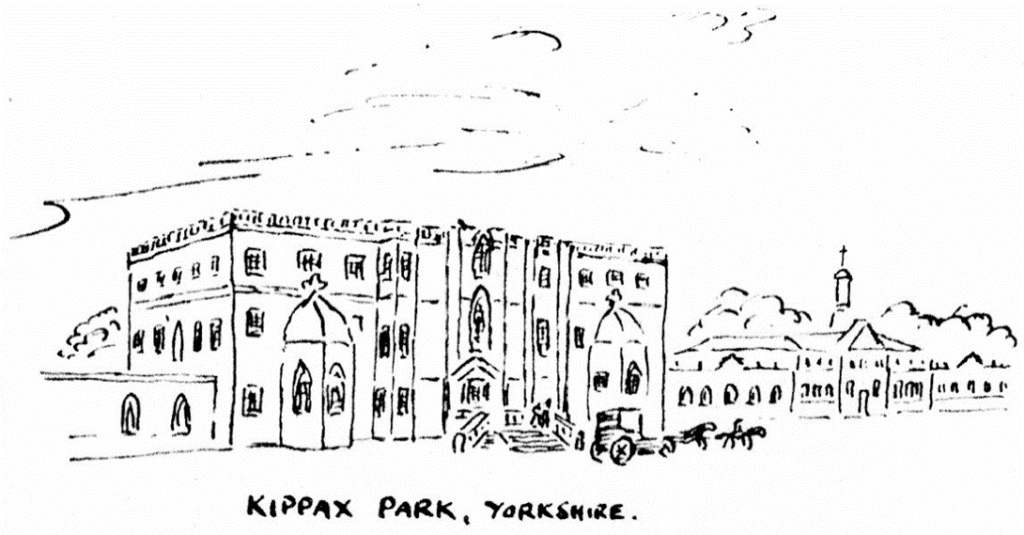

By 1881, the people of Bowers Row were losing sight of a memory the memory, if it had ever been told them, of a Catholic chapel which, twenty, or so years previously, and probably before most of them had come into the district, had existed quite close by, at Kippax Park, of all places, the home of the Bland family. The copies of the “Laity’s Directory”, which eventually becomes the “Catholic Directory”, from 1824 to 1849 record the existence of a Catholic chapel, open to the public although not licensed for weddings, at “Kippax Park, near Pontefract”. The priest named in the Directory as serving there for the first five years was a Rev. M. Reculet. I hazard a guess that this is the Louis-Felix Recuillez who was one of the French priests who fled the French Revolution, took an oath of allegiance to the English Vicars-Apostolic, and settled permanently as “missioners” in England. 5. By 1829 he had been replaced by Fr. John Bell, who is listed in every year up to 1843. After a short gap, he in turn was replaced by Fr. Thomas Middlehurst, who had previously been at “West Witton, near Bedale”. Fr. Middlehurst is listed until 1848 inclusive; the entry for 1849 simply states the existence of the Mass-centre, and after that there is no further mention of Kippax Park as a chapel. It may or may not be significant that the owner, Thomas Davison Bland, died in November 1848, and was succeeded by his eldest son with the same name. Or possibly the chaplains were elderly men and the needs of the town congregations prevented their being replaced when they died.

What sort of congregation could the Kippax Park chapel have? It would probably be fairly small, consisting of the R.C. members of the family, their guests, those of the servants who were Catholics (like the Boston family at Kippax Lodge), as well as any Catholics living in the vicinity and there were some – 6. William and Mary Beevors of Allerton Bywater, Charles and Mary Hewitt, the Heys, the Austins and the Lockes, all of Kippax. (The Lockes were coal-owners of Kippax, connected with. Gill & Warrington of Normanton.)

But the Blands were staunch supporters of the Church of England, so how could it come about that the Bland family home should house an R.C. chapel ? Our diocesan archivist explained to me that this, the first Mass centre since the Catholic Relief Act of 1778 to start within what is now our parish, was the result of the marriage between Thomas Davison Bland, of Kippax Park and the patron of the Kippax Parish Church, and a lady named Apollonia Mary Stourton, daughter of Lord Stourton of Allerton Mauleverer, near Knaresborough whose family were Catholics of long standing. They married in 1812, and when they set up house at Kippax Park, Mrs Bland established a Catholic chapel there and maintained a resident priest for over 20 years. Their sons followed their father’s religious tradition, and the daughters followed the mother a practice which the priests would tolerate only because there was little else they could do. Edward, one of the younger sons, in fact became Vicar of St. Mary’s, 7. while the eldest daughter, called Apollonia after her mother finished up building a Catholic church. She never married, and she went to live with a younger sister, who had married a Mr Charles Weld, himself connected with the Arundel-Howard-Norfolk family. The Welds lived at Chideock Manor in Dorset, and it was from there that Miss Bland wrote to Bishop Cornthwaite in February 1871, explaining that she wished to give £1000 to build and equip a Catholic church at Castleford, for the benefit of the Roman Catholics there — obviously by now the pattern of increasing and incoming population was being repeated in Castleford. Bishop Cornthwaite was in charge of Roman Catholic affairs for the whole of Yorkshire, and his title was “Bishop of Beverley”, although he lived first at York and then in Leeds. On receiving Miss Bland’s letter, he replied from Leeds, thanking her for her very generous offer, but saying that funds were already available for a church at Castleford. Apollonia then remembered an advertisement appeal made by the priest at Stokesley, near Knaresborough. Bishop Cornthwaite accepted her second offer, and used £1000 to build and furnish St. Joseph’s, Stokesley, in 1873. 8.

The church at Castleford was, in fact, built through the good offices of Mr Richard Austin, of Fryston Hall and Carlton Hall, who owned a large amount of land in the area, and who was connected with the Kippax.

In those days there was great opposition to the purchase of land by Roman Catholics for building churches or schools, and a friendly landowner was a great help. Castleford St. Joseph’s began in 1877, but its baptismal rs start at 1881, possibly because the priest at first lived at St. Joseph’s, Pontefract and may have kept the records in Pontefract while commuting to Castleford for services. The first priest to serve the new ford “mission” was Fr. Gustavus, J. Thonon, 9. but he, within a few years, became assistant priest at St. Patrick’s, Bradford, and Fr. John on came from St. Marie’s in Sheffield to start his 56 years in Castleford. (It is possible that a little time was needed for things to settle following, in 1878, the division of the Beverley diocese into the diocese of Leeds and of Middlesborough). In these days, the title “parish was not in use Fr. Hewison signs his baptismal records with me and the title, abbreviated, “Miss.Apost.”, with the old-fashioned “S” the title can be translated as “the priest appointed to this n”, and illustrates the sense that the Catholics were still feeling their place again in this country.

Just about this time, Joshua Bower went bankrupt. The pit was closed between 1878 to 1880. This bankruptcy perhaps explains why there are no reliable records of Bowers accounts, which makes it so difficult to put a date to the building of the pit houses. Those must have been two very hard years for the Bowers people, and it does occur to me to wonder if the lack of work drove away some of the earlier inhabitants, who seem to have little or no trace behind them. That, to me, is simply another example way in which finding the answer to one historical question seems lead to yet another question.

Tough years or not, there was too much demand for coal for it to be left in the ground – in 1880, the mine opened again, this time as JW Bowers

“A perfect English gentlemen from York” is the description given to

Canon Hewison by one who grew up knowing him. I get the impression of a man with an air of aloof authority who might, these days, be called “paternalistic”. Whether that is a true impression or not, this convert from York certainly worked hard to build up his parish and care for his people, singlehanded from 1880 until 1910; in that year the Rev. Johann Theodore Donkers became his “missionary co-adjutor” (“curate” for short). Father Donkers was a young Dutchman, born in Uden in the Brabant area of South Holland, who trained at Ushaw College, Durham, and was ordained a priest in July 1910. He already had an uncle in the diocese, Fr. Theodore Van Zon, and a brother, Fr. Willibrord Donkers. Castleford was his first appointment and he worked there for seven years, followed by ten years as curate at St. Joseph’s, Bradford, then parish priest first at Woodlands, near Doncaster, then at Bradford St. Peter’s, where he celebrated his Golden Jubilee in 1960 and died in 1965, still in harness at 80 years old.

Fr. Donkers took up his post and soon began to take a special interest in the Bowers Row area, doing a paper round every week to make sure that each family had a copy of the “Universe”; and using Number One, School Street as a base for an every-Friday-Sunday-School. (This continued the habit of Canon Hewison, who in the preceding years would take a weekly horse taxicab to Bowers School, take a class there, call on the R.C.S. then walk home. The Canon took catechism in No. 1 School St. or in any RC house where they would let him. If the women were all cooking or washing, or the men bathing after work, he would take RE classes in the open air).

Fr. Donkers gave every encouragement that he could to the plans that the Bowers Row people had for building themselves a church and these plans were put into action with vigour. There were dances and socials at Bowers School and anywhere else that could be found, collections made from door to door which nobody refused, whatever their denomination, sales of scent cards at a penny each, and any other fund raising scheme that could be dreamed up, including the sale of ham sandwiches, with home-kept and home-killed ham, boiled in a setpot!

The money was handed to Canon Hewison for safe keeping. The Canon used it very well, to help finance his new Catholic school in Castleford ! But the Bowers Row people, though rather dismayed, were not deterred. They made use of the new Catholic school, and carried on collecting for their own new church, helped by the chapel people with whist-drives and collections, to such an extent that it was said by the Catholics that “it was those who were not Catholics who built the church they never refused a thing”. This time, in 1914, the Canon bought the site, along Preston Lane on the edge of Brigshaw Wood. The site was levelled by men of the district, plans drawn up by Mr Arthur Hartley, and the work put in hand by Mr Gus Gallagher, who remembers the “whacking good tea” at the stone laying ceremony. The buttresses were splayed to distribute the weight of the small but “substantial brick structure”, and the whole building was in accordance with building regulations laid down for this area at that time. A concrete raft foundation was not, in those days, considered necessary, and the church rested on three rows of bricks laid directly on to the clay bed. The church was pleasantly simple, possibly reflecting the simple taste of the people who had it built, and certainly reflecting the absence of surplus money.

The phrase “Gothic in style” in the newspaper reports seems to me to be a stretch of the imagination St. John’s has a pitched roof, a pointed chancel arch and tympanum light, and the open woodwork supporting the roof has a few pointed joints but I cannot see how these can earn a building the title “Gothic”. Possibly the Canon either spoke to the reporter with a twinkle in his eye, or else was unconsciously expressing a wish to be linked with the medieval-style revival fashionable in his youth. Whatever we say, St. John’s remains small, unpretentious, simple, homely in the good sense, and with a welcoming atmosphere. But not Gothic. The description of the seating accommodation is also highly optimistic – we can seat 105 people in reasonable comfort, not 130. I’ve so far been unable to discover why the church is dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, although I find it a suspicious coincidence that both priests at Castleford were called John.

The windows of painted glass, all of the same style and pattern, puzzle me a little – I am told that the ones over the altar and the entrance were the original windows when the church was opened in 1916. But the references to safe return from the Great War imply that some, at least, of the nave windows could not have been fitted before 1918. The mystery remains, for the time being, but as least we know who the people are who are mentioned in glass – Sharah Shillito was Canon Hewison’s housekeeper, Mary Horan was his maid, Esther Barron came from a Methley family who supported St. John’s, walking each Sunday over the Ha’penny Bridge; the Needhams were Castleford family who supported St. John’s, the Gallaghers were its builders; the Greaneys were pillars of the parish at Bowers Row, and Thomas Wigglesworth helped to build the church before becoming a Catholic he channelled the help that came from the people of Bowers Allerton Mission Chapel, and his daughter, Mrs Bickerdyke, played the organ at St. John’s; the Conelly boys all came back safely from the War, one of them with the Distingushed Conduct Medal; William Needham did not come back from the War, neither did Peter Mills, nor Peter and Patrick Hession, whose brother Tommy remained in the mine and married the sister of Peter Mills.

The Mills had come from Lancashire to live in School Street. Mrs Mills was one of the stalwarts who worked to finance the building of the church nobody refused, even though when she asked for donations towards the original Stations of the Cross, many people thought that they were being asked to support something to do with the local railway.

The Mills were just one of a number of new names that start to appear in the baptism registers after 1905. Of course, many names appear only once or twice, while other names occur regularly throughout the first 25 years of the Castleford records, and beyond. The records show that Catholics lived, as well as in Bowers Row, Hollinhurst, Allerton, Great Preston and Kippax, in cottages at Fleakingley Beck, Newton, Ledston and Ledston Engine. A connection that I find particularly interesting is to see in the Aberford records that William and Mary Beevors of Allerton Bywater were communicants at Aberford in 1866, and, from the Castleford records, that William and Eliza Beevors of Allerton Bywater had their infant daughter Mary Jean baptised at Castleford in 1890.

Swillington does not appear on our scene until 1919 Joan Elizabeth Westmorland of North Lodge is the first baby from Swillington named for certain in Castleford’s records the village had long since forgotten the Dineleys and their efforts to keep alive the traditional faith, as Ledston had forgotten its Withams and its Websters, Shellitoes and Ellises, and Kippax had forgotten its Ledes, its Vavasours, and its Haldenbys.

Father Donkers stayed with the Canon for seven years, the first and the most long-lasting curate that the Canon ever had. Quite a few others did not last any such length of time since the Canon was a man of his day and maintained his position with vigour. In those days it seems that bishops did not define parish boundaries this was done by the parish priests themselves by a system of mutual disagreement. To quote Mrs Mary Jordan (Miss Darwin, whose parents came from Barnsley in 1907): “When we lived at Leventhorpe Lodge in 1914, we were visited by Fr. White from Hunslet, the Oblates from Mount St. Mary’s, Fr. Donkers on his bicycle from Castleford every Friday, and Fr. Baines from Aberford, who all claimed that we were in their parish!” The cycle riding was the explanation that Fr. Donkers had for his missing right ear-lobe; he said that he lost it through frostbite, from cycling round the Bowers Row area in bitter winter weather.

He was appointed to Bradford in 1917. He said himself that Canon Hewison asked him to stay on with him at Castleford, promising to hand the parish over to him when he retired or died Fr. Donkers, perhaps foreseeing that he would have another 19 years to wait, politely declined the offer, leaving the Canon to “go through curates like cigarettes”. He was succeeded, one after the other, by Fathers Valkenburg, Cuniffe, Moynihan, Whitehead, Reynard, Sole, William O’Grady, and Fred Bennett. In 1935 Fr. Reeves was added to the staff, and Canon Hewison died on the first day of January, 1936. Fr. Comerford took over, with Frs. Bennett, Stoker, George Collins, and Matt Farrelly, three priests at a time.

By this time the pattern of population in the area served by St. John’s was clearly emerging the area was developing as coalmines in other parts of the country began to close down – this is the pattern which continued until not long ago. In 1921 a coalminers’ strike sent the small first wave of Durham people to live in Swillington. In 1922 the closure of the mines in Gloucestershire sent the Woolford family to Allerton and the Bowers Mission. The General Strike in 1926 re-enforced the flight from County Durham members of the Healy family came to Swillington from Annfield Plain, following the earthy advice of their Durham pit manager. The Morgans and the Jordans, the Bills, the Finerans and the Johnsons, all fled Durham for the Yorkshire coalfields.

Similar events in the Lancashire pits brought the Smith, Sherington and Meeson families into the area. This larger wave of movement persisted and grew greater by 1929, following the slump in the U.S.A. The coalmines of Maryport and Whitehaven in what is now Cumbria closed down, so the Irvings settled in Swillington. Up till then Swillington had consisted of (apart from the Lowther estates) just the church, the school, the almshouses and a few farms and cottages. Now it began to develop, and quite rapidly. Most of the newcomers to “Little Durham” felt welcomed, since those to whom at first they were strangers in their midst, had at one time themselves been “strangers in the land of Egypt”. 10.

Miss Darwin, who lived at 28 Park Avenue, Swillington, and taught at Preston School, gave religious lessons in her home for the Catholic children of Swillington, in St. John’s for the Woodend children, and during the Scripture period in the porch at Preston School. Swillington people used to come to Sunday Mass at St. John’s by walking over Fleakingley Beck to Great Preston then down to Woodend. Later they had a special bus, driven by Mr Naylor, from Swillington each Sunday, through Astley, picking up along the way.

Meanwhile, Allerton was developing, too. T. & R. W. Bowers sold out to Pease and Partners about 1930. This, too, was a North-East firm, from Darlington, which brought its own officials. The building line beside St. John’s began to fill up the church had neighbours close at hand, at last. Mrs Brooks, just below the church, was in great demand, for First Communion breakfasts, May Procession teas, or weekly hot water for cleaning the church, and later for children’s instructions. The house just above the church, now used as the priest’s house, was built in 1933 for Mrs Dyer, who up till then had kept the grocery-Post Office in Bowers Row. She had an injured arm, and to allow her coal to be delivered direct to her back door, Canon Hewison let her use part of the church land as a driveway; twenty or so years later, this would be the cause of a bitter dispute when the next owner of the house demanded the same as of right; another ten years or so later, the argument was finally settled when the diocese bought the house.

Then, in 1936, Canon Hewison died. He was succeeded by Fr. Comerford, who, after a while, began to have Sunday Mass said at Swillington as well as at St. John’s, the priest travelling from Castleford to each place. For two years Mass was said at the Swillington Hotel, through the kindness of Mr & Mrs Bickerstaff, and then in the Miners’ Welfare, throughout the period of the 39 – 45 War and up to 1954, on a trestle table raised on wooden blocks brought from Primrose Pit. (The assistant priests included Frs. Farrelly, Creed, Belton, Roche and Townend). By this time, apart from all the world-wide movements of population, a smaller one took place, closer to home the Victoria and Albert Pits closed in 1948 and Bowers Row began to be demolished in 1951. Coalmining had been a nationalised industry since 1947. Kippax Park was demolished in 1953, but house- building was re-started in all the villages of the area.

Anyone looking at Bowers Row now will see a clothing factory, a mission hall, and a vehicle depot. The mission hall still does what it was designed to do, although its congregation no longer live on the doorstep; the clothing factory includes all that is left of the school, and the vehicle depot stands on the site of some of the houses only the dropped kerbstones remain to indicate that once there were streets here. Where the Johnny Pit and the Star Pit used to be, is now the immense crater of an open cast site.

The demolition was a gradual process, and people did not move very far. They moved to new houses in Swillington, to a new estate in Great Preston, and to the new N.C.B. estate off Station Road in Kippax. By now Fr. McGee was parish priest at Castleford, with plans for providing more facilities for the Catholics of the area he had the chance of some land, with the option of building a school, off Wakefield Road at Swillington. Against his better judgement, he was persuaded not to buy it persuaded by people who, later, bought it for themselves, much more cheaply, or so I am told. Instead, he bought a piece of land off Astley Lane, and the chapel-of-ease was built there, dedicated to Our Lady, Help of Christians. This was a dual purpose building by Poskitt’s of Airedale, designed to be both a Mass centre on Sundays and a social centre during the week. The year was 1954, and soon after Swillington chapel was opened, Fr. McGee got a letter from Bishop Heenan of Leeds.

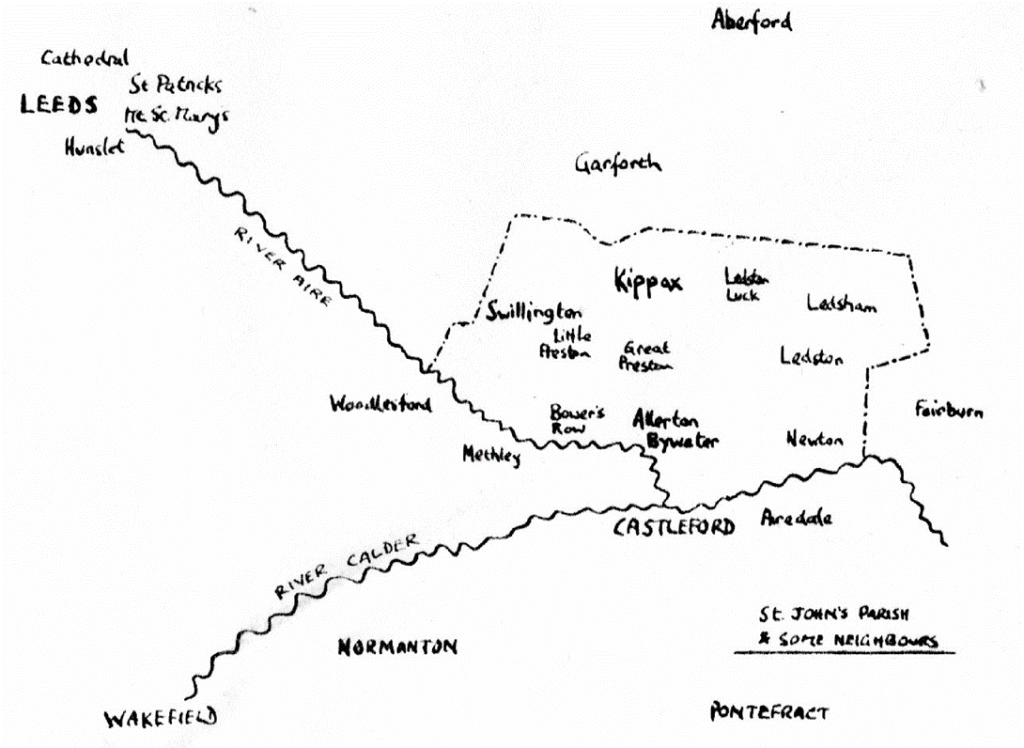

It was 1954, and a wind of change was now sweeping across the See. Fr. McGee was informed that part of his parish was being cut off and formed into a new parish, based on St. John’s, Allerton Bywater. The new parish would consist of Allerton Bywater and Airedale, leaving Swillington still as part of Castleford parish! Fr. McGee rapidly got in touch with the Vicar General who managed to persuade the Bishop to study the map. As a result, Airedale stayed with Castleford for the time being, and the now independant daughter parish, St. John’s, was given into the care of Fr. Kieran Kehoe, with responsibility for looking after Allerton, Swillington, Great and Little Preston, Kippax, Ledston Luck, Ledston, and Ledsham (also Fairburn until 1962, when it was found best to hand this over to the new Knottingley parish).

At first Fr. Kehoe had to lodge at the presbytery in Castleford, until the diocese bought a house for him at 56 Preston Lane, nine doors above the church. He threw himself into the task of getting the new parish on its own feet. His previous appointment had been as a curate at St. Patrick’s, Huddersfield, where he knew a joiner called Charlie McNulty. Mr McNulty came over and fitted the sacristy with oak dressers and cupboards, while pine benches were bought to replace the old kitchen chairs in St. John’s. Fr. Kehoe had plans drawn up in 1957 to extend St. John’s and to provide confessionals, a baptistry, a cloakroom and a choir gallery, but these never materialised, possibly because planning permission could not be obtained. since the extensions would have projected beyond the building line. Obviously, the parish was growing.

The parish hall was the Swillington building, beautifully kept with a brick-paved pathway, parking for half a dozen cars, flowerbeds, and two well-kept lawns. Social functions were held inside, and garden parties outside. Villagers started to use the grounds as a short cut, so plans were drawn up for a brick wall with wrought iron gates. The plans remained as plans, for Fr. Kehoe was transferred to Cleckheaton, in 1960.

Fr. Robert Warren had his own plans when he took over at St. John’s a hall and presbytery along the new Brigshaw Drive. The two were planned together as two parts of a whole. The Hall was built for £12,000, and the presbytery begun alongside, but lack of certainty whether or not the presbytery could be paid for caused the diocese to abandon the idea, and the site was levelled, leaving an empty space between the church and the hall, which was used as a car park. (The parish had originally owned even more land than this site, since some parish land was sold to Garforth U.D.C. for them to build some of the bungalows along Brigshaw Drive).

By now, building was going ahead rapidly in the district, especially in Kippax, which all of a sudden found itself an area suitable for development.

In fact, development was in the air everywhere Vatican II was beginning to be put in motion. The development of the revised rite of the Mass began in Fr. Warren’s time and continued with Fr. Patrick O’Keeffe, who took over on Fr. Warren’s retirement in October 1966. The final phase of the new rite took place early in 1970 by now the Mass was said facing the people, using the simple wooden altar which had been made for St. John’s by Mr Tommy Hudson. (Swillington would wait till 1974 before having Mass facing the people).

When Fr. O’Keeffe arrived he was faced with a big debt. Soon he had moved house, from 56 Preston Lane to number 40, next door to the church and therefore in many ways much more convenient, but in a poor state of repair. He began the thankless task of trying to extend, repair, and make the house suitable for its new role, and improved the now much- needed car parking facilities, but, knowing that the Church consists of people rather than buildings, he concentrated on serving the people, making himself all things to all men, finding great friendship with the people of the Bowers Allerton Mission Chapel. He cleared the debt, I’m glad to say, which must have entailed very hard work for the layfolk who supported him, as well as for himself. But it was done. On his appointment to St. Peter’s, Bradford (where Canon Donkers had been), he handed me the keys of the kingdom, at the end of September, 1973. On my first Sunday here I found St. John’s bursting at the seams.

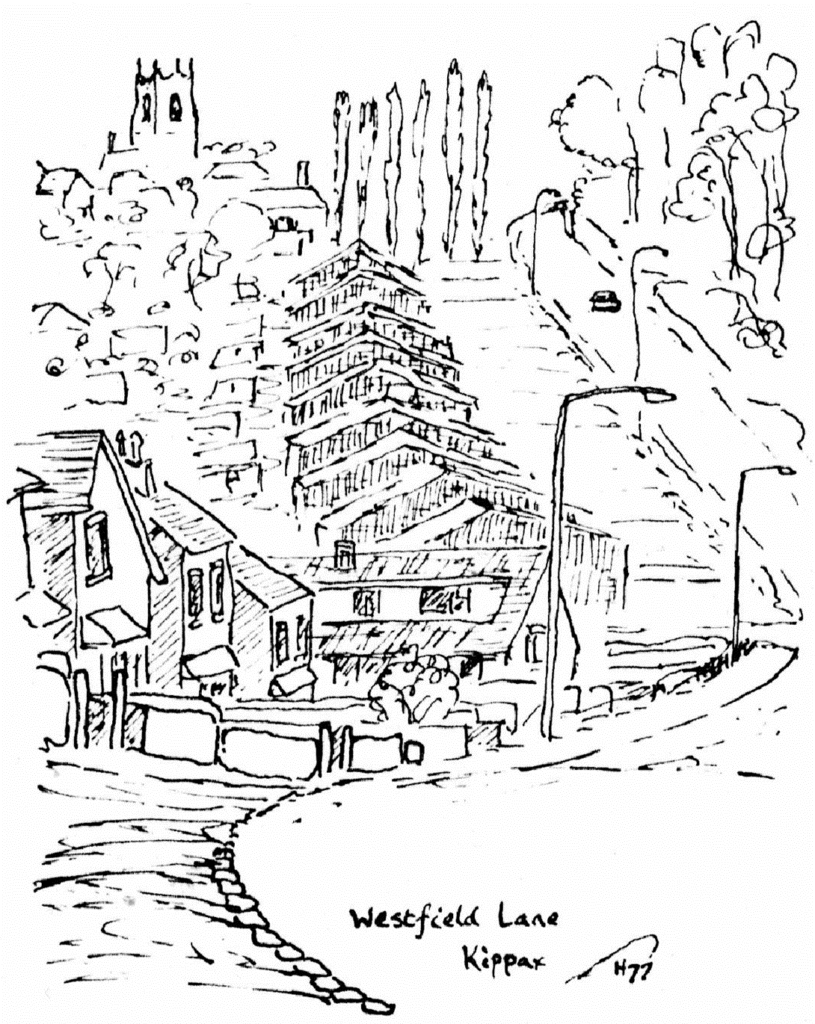

I think we can credit Kippax for the overcrowding, since by 1973 it had become almost a dormitory town for Leeds, instead of the pit village that once it had been. The Coronation area was built up about 1953, the N.C.B. estate was occupied about 1954, along Westfield Lane a stream and a turkey farm gave way to new housing, Oxford Drive area was built about 1964, the estate on Kippax Common from around 1966, and the Pondfields development shortly afterwards. General shortage of money slowed down. the building programme, but did not halt it. The enforced move into Leeds Metropolitan District merely altered the direction of the building programme.

All this meant that more people were coming into the parish, many again from the North East, most from Leeds, and some from all corners of the British Isles. All available space in St. John’s was adapted for extra seating, but even this was not enough. St. John’s could not hold its Sunday congregations, even with two Masses, and Swillington could no longer cope. The parish had, reluctantly, almost decided to build a gallery within the tiny church, which admittedly would have spoiled the building, when we received a generous offer. The Vicar and the Parish Church Council of Kippax St. Mary’s startled us with the offer of the use of their church on Sunday evenings, even to the extent of being prepared to alter their own timetable. This was Christian hospitality indeed – “Love the stranger, then, that is in your midst, for you yourselves were once strangers in the land of Egypt”. 11.

The Vicar felt, and the P.C.C. agreed, that it was part of their Christian duty to help to make all newcomers, whatever their denomination, welcome to the township, and, since each of the three Sunday Masses was intended for all the Catholics living anywhere within the area of St. John’s parish, as well as the direct benefit intended primarily for Kippax, other Catholic people from St. John’s parish could equally well use the opportunity if they wished to do so. Both the bishops were consulted, then a referendum was taken and the offer was gratefully accepted.

The first service was held on February 2nd, 1975, when Candlemas Day happened to fall on a Sunday there was a short prayer of introduction from the Vicar in St. Mary’s Hall, where members of both St. Mary’s and St. John’s were gathered. We formed into a candlelight procession, all of us, and St. Mary’s congregation led us, singing, into Kippax Parish Church. Mr Darvill gave a short address of welcome, and we carried on straight into the “Glory be” of the Mass of the day. A small portable wooden altar had been specially made so that the celebrant would face close to the people, and the Mass equipment had been got through the kindness of well-wishers both within the parish and from outside.

The experiment has proved very much worthwhile, and we have continued to be the guests of St. Mary’s, having evening Mass there each Sunday at 6-30 p.m. The hospitality of the parish church and the offer of the use of St. Mary’s Hall should prove even more worthwhile as time goes on and development continues – already the new Mount Pleasant dwellings are being occupied, and house building is going on rapidly behind Tatefields.

The pattern of movement into the parish may have altered, but the fact of movement into the parish seems to be continuing. Up to, say, ten or even less years ago, the moving of people into St. John’s parish was usually the result of some coalmine closing down in another part of the country, and the incoming worker still had a great deal in common with the parishioners already established here. Nowadays, all the villages in the area are developing as homes for people with many different ways of earning a living. Again, in the old days, people who came into the area could return to the scenes of their childhood only rarely, when they had saved the rail fare, but nowadays people who have moved here from other parts of the country often have their own cars and can go back for week- ends to their old haunts. Even more so, folk who have moved here from nearby cities naturally feel their old roots pulling them back and they can easily keep in touch with their old friends. It may be that any real loyalty to the parish may need at least another generation to develop.

All this makes it all the more difficult to build up a loyalty to the present parish, especially since all the Catholic schools that we use are outside our territory. (Every pastor knows that if he can gather the children of his parish in some project, he can be sure of a large audience of parents and relations enjoying their pride in them. But our children are scattered throughout thirteen different schools and six different home communities). Nevertheless, an attempt must still be made to form some sort of parish feeling. In fact, more than ever is there the need to “love the stranger since you were strangers in the land of Egypt”. 12. Every parish is described as being “a corner of the Lord’s vineyard”. St. John’s was never designed as a planned garden, its growing plants were not deliberately planted; it seems to me that if it is to be described as a garden, then it is almost a garden by chance, since most of its flowers have sprung up because they were blown there by the wind of necessity. But for all that, with a little cultivation there is no reason why the blooms should not flourish.

Other things are needed, of course, as well as the cultivation the part of already established families, there is needed the willingness to accept newcomers into their midst and to give them a genuine welcome; on the part of the newly-arrived families there is needed the willingness to be accepted as both part of their own village and as part of the parish community; everyone within the parish has a worthwhile contribution to make, whether they have lived here for all their lives, most of their lives, or only a little while.

The sense of parish community which is possible in a city parish will it may not not be readily achieved in our collection of scattered villages be achieved to the same extent at all but we may well, with some effort, achieve a limited feeling of parish community which is valuable and essential as far as it goes.

Within each of our own local village communities we can help to make Christ present in our midst, less by our words, more by our lives among our neighbours. This may sound like a summary of part of the teaching 13. but what I find of the Second Vatican Council, and indeed it is interesting is the similarity between this modern expression of the Church’s teaching and the tone of the sermons of a priest who preached in London in 1785, 14. if I may end by quoting Father James Archer :-

“Remember that,

notwithstanding the varieties of customs and opinions, all your fellow-creatures have a claim

on your benevolence;

all should be dear to you;

because all are made after the image of God,

all are redeemed by Christ’s blood.

Let then, your active and spirited exertions, your honest industry,

contribute to public happiness.”

“I wish to see all men,

however various their religious creed,

mutually loving,

cherishing

and assisting one another,

and walking through the chequered paths of this mortal life

in harmony and peace.”

Gerald Hargreaves,

St. John the Evangelist,

August 24th, 1976

REFERENCES:

1. Baines, “Yorkshire Past & Present, 1870, pages 52 & 53.

2. Baines, pages 102 and following.

3. Beresford & Jones “Leeds & Its Region”, page 189, and census returns supplied by Mr John Goodchild. The actual figures for Great and Little Preston Township, which covers the Bowers Row area, are as follows:- 1801, population 413; 1851, population 464; 1861, popula- tion 541; 1871, population jump to 1100; 1881, further population jump to 1526.

4. This section derived from John Bossy’s “The English Catholic Com- munity, 1570-1850”, published 1975.

5. Bossy page 356.

6. Parish records of St. Wilfrid’s, Aberford.

7. Manuscript written by William Bywater, Town Crier of Kippax, kindly loaned by Mr Francis Bellwood.

8. This section from Leeds Diocesan Archives, and from David Allen’s “St. Joseph’s, Stokesley, The story of a Catholic parish”, centenary booklet, 1973.

9. Catholic Directory for 1881.

10. Book of Deuteronomy, chapter 10, verse 19.

11. again Deuteronomy ch.10, v.19, with Exodus ch.12, v.48.

12. once more Deuteronomy ch.10, v.19.

13. “Gaudium et Spes (Joy and Hope) the Church in the Modern World”. 1965.

14. John Bossy, pages 378 & 380, quoting Archer.

The references in chapters 4 & 5 to the surnames Hammerton, Dineley, Witham, Webster, Shellitoe, Ellis, Ledes, Vavasour and Haldenby, and to the Catholic School in Castleford in 1590, are all taken from Hugh Aveling’s “The Catholic Recusants of the West Riding of Yorkshire 1558 – 1790”, published by the Leeds Philosophical and Literacy Society.

THANKS

A friend once told me that historians often want to write a history that will be the last word well, I’m not a historian, and this little booklet will not be the last word there are some sources that I have still to look into, there may be mistakes, and there will be omissions; in fact, one regret is that I have had deliberately to leave out many little stories which interested me but which might have sidetracked the main theme.

The Bishop’s kind foreword talks of my “taking great trouble”, but, in fact, it was no trouble at all since it was most enjoyable and quite fascinating. For that I have to thank many people, among whom are the following:-

Dr. Robert W. Unwin, B.A., Ph.D., of Leeds University and Great Preston, for his guidance and encouragement from start to finish;

Fr. George Bradley, the archivist of the Leeds Diocese, for his expert advice. and valuable information;

the staff of Kippax Library and Castleford Library, Fr. Placid Spearritt of Ampleforth College Library, and the staff of Wakefield County Library, especially Mr. John Goodchild;

the staff of the Pontefract & Castleford Express for their kind co-operation, clergy, past and present, of different denominations, for their recollections, advice, and the use of parish records;

parishioners, past and present, especially members of the older families, for their recollections;

Mr & Mrs J. Rushton of Bowers Allerton Mission;

Mr Francis Bellwood and Mr Sam Cheeseborough, of Kippax;

Mrs K. Winn & Mr L. Lynch for the loan of photographs of parish events; Mr A. Holmes of Swillington for the loan of his fine photographic records of the Bowers Row mines and houses;

the Bishop for his interest;

and all who have given encouragement.

If any dedication is needed for this account of the past, let it be to the present and the future “people of the parish”.